The Eurovision voting system is in question now more than ever. Countries such as Norway, Finland, Belgium, Slovenia and Spain have all called for a thorough review of the voting system to ensure fairness, and that the result represents the public’s opinion.

The main focus is currently on the televote, namely after Israel carrying out a targeted mass-advertising campaign and going on to win the televote at this year’s contest. However, for many years broadcasters have also been questioning the fairness of the jury vote at Eurovision.

At Eurovision 2015, Il Volo had secured Italy’s first ever televote win, but ended up in third place after a strong jury push for Sweden. One third of the popera trio, Piero Barone, told wiwibloggs that he thinks that the weighting should be adjusted, pointing out that “the televote are the people who buy the album and come to your shows.”

In 2019, we saw the largest ever discrepancy between the televote winner – Norway’s KEiiNO – and its corresponding jury ranking — a mere 18th place. Band member Tom Hugo expressed his dissatisfaction with the jury system, commenting “it is subjective what is good and bad, and then it is strange that a few people should sit and decide half of what a country should give as points”.

Later that year, the Spanish head of delegation revealed that the EBU were looking into altering the jury-televote system, although in the end no changes were made.

From 2009 to 2014, the jury and televote only disagreed on the winner once (in 2011). However, when we take 2015 to 2025, the jury and televote have only agreed once (in 2017). Theoretically, with the 50:50 split, juries have just as much power as televoters at Eurovision. However, for the past three years in a row, it has been the winner of the jury vote who has ended up winning the whole contest, whilst the viewers’ favourite has gone home empty handed. What’s more, some are complaining that the winners are becoming predictable and following a similar jury-pleasing formula.

Many have speculated that Eurovision jurors favour certain types of entries over others – namely favouring the more ‘serious’ entries that focus on powerful vocals, and shunning the more ‘fun’ entries with hit potential. In this article we will be investigating if the juries do indeed follow certain voting patterns, and explore ways that the EBU could tweak the jury system to give a result that more accurately represents the people’s favourites.

Eurovision juries: Who, what, when and why?

When Eurovision started back in 1956, scores were decided exclusively by a two-person jury from each country. Although the size and format of juries fluctuated, the 100% jury system prevailed until 1997, when technology had advanced sufficiently for five countries to vote by televote. From then until 2008 it was the televote that reigned, with audiences at home exclusively deciding who received their douze points, and juries only being used in exceptional circumstances.

However, due to repeated complaints of regional voting, juries were re-introduced in the 2009 contest, with 50% of a country’s score still determined by viewers at home, but 50% also decided by a national panel of 5 music professionals. Hence, in the 2010s we experienced a shift from countries sending songs purely to please viewers at home, to countries catering also to please national juries. Eurovision still uses this 50:50 jury-televote split today.

The juries are made up of five music industry professionals selected by each country’s competing broadcaster. They aim to include a well-spread mix of ages and gender, featuring the likes of musicians, producers and radio DJs.

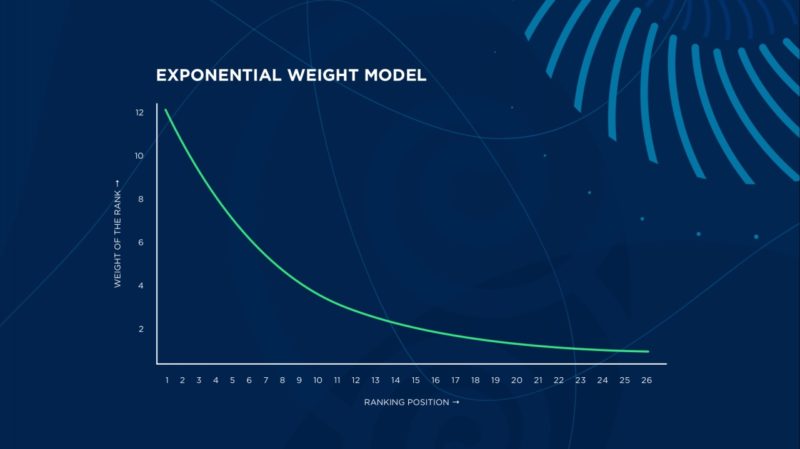

The five jurors rank each entry from favourite to least favourite, and their points are combined in order to work out an overall ranking. Note that, since 2018, an ‘exponential weight model’ is used. This means that a juror ranking an entry high has great impact on its overall ranking, but ranking an entry low has little impact. Theoretically, this benefits bold or divisive entries and avoids middle-of-the-road or inoffensive entries ending up with the highest averages.

Whilst there were accusations of corruption throughout the 2010s, this has generally been smoothed over after six countries had their jury votes annulled in 2022 following a vote swapping scandal. However, this misconduct (as well as Azerbaijan qualifying despite a nul points in the televote) did lead to the EBU changing the semi-finals from 50:50 jury-televote split, to 100% televote at the 2023 contest.

Whilst it was initially feared that this would disadvantage smaller nations with fewer voting friends, it has generally been considered a success. We have gone on to see microstates like Malta and San Marino qualify, and countries with historically strong televote support, such as Serbia and Romania, staying in the semis. Therefore, in this analysis we will just be looking at the grand finals.

Data analysis: Do juries really favour ‘serious’ songs?

In order to investigate the theory that juries favour serious songs over fun songs, we are going to get mathematical. We have created a spreadsheet with the split jury and televote points from the grand finals of the past five editions of Eurovision.

By doing this, we can work out the difference in the quantity of points given by juries vs points given by the televote, and work out if there are indeed any patterns. If both the juries and the viewers at home loved or hated an entry completely equally, their difference would be 0 – aka, zero difference in opinion.

Note that our analyses exclude Ukraine’s results after the 2021 contest (following the 2022 full-scale Russian invasion) and Israel’s results after the 2023 contest (following the 2023 Israel-Palestine conflict), to avoid geopolitical events impacting the results.

In order to determine patterns in jury voting, we have labelled each entry as either ‘serious’, ‘fun’ or ‘other’:

‘Fun’

- Upbeat, either in the sense of a happy sound, danceable production or humorous lyrics.

- Happy, energetic, or humorous visuals that intend to make you smile or dance.

- The performance is more likely to draw attention to dancing over impressive vocals.

‘Serious’

- Most likely ballads or mid-tempo songs, with either a sad or mysterious overall feel.

- Most likely little smiling or visuals that emote the feeling of happiness; the singer takes themselves very seriously.

- The performance is more likely to draw attention to impressive vocals over dancing.

‘Other’

If a song doesn’t fit into the ‘serious’ or ‘fun’ category, it could be for a variety of reasons, such as:

- The performance mixes elements of ballad and up-tempo (eg. Austria & UK 2025).

- The song is dark or experimental, but is mixed with fun or camp visuals (eg. Poland 2025, Iceland 2019).

- The song is up-tempo and radio friendly, but with a more serious overall vibe (eg. Sweden 2018 & 2024)

- The performance is high energy but doesn’t necessarily make you smile or dance (eg. common in rock entries)

Please note that we recognise that it is impossible to categorically label entries as ‘fun’ and ‘serious’. We have tried our best to use this criteria to give the most accurate result possible, but it will still not be perfect and must be taken with a pinch of salt. This article is purely a fun project of a Eurovision nerd who wanted to test a theory!

The results

Below, you can find showing the results of jury-televote difference from 2021-2025. Results from post-war Israel and Ukraine (as explained previously) are written in italics and excluded from total and average calculations.

Patterns

An asterisk* denotes that the result is excluding post-war Israel and Ukraine (as previously explained).

Overall: a clear jury preference for ‘serious’ entries

The first thing we find is that, every year without fail, juries have had an overall damaging impact on ‘fun’ entries. On average, juries give each ‘fun’ entry about 26 points less than the televote does. When you add that up, that makes an average of roughly 239 points less than televoters per grand final, ranging from -71 points less in 2021, to -427 points less in 2023. So over a five year period, juries have hurt ‘fun’ entries by a grand total of 1196 points in comparison to viewers at home.

In contrast, the jury has helped ‘serious’ entries every year without fail. On average, juries give every ‘serious’ entry roughly 48 points more than televoters. Added together, this gives an average boost of about 392 points per grand final in comparison to the televote, ranging from +199 in 2024 to +664 in 2022. So over the past five years, the juries have helped ‘serious’ entries by a whopping 1958 points, compared with the general public.

The most extreme disagreements

Below you can find a list of the biggest jury-televote disagreements of the past five years.*

- Finland 2023: -226

- Moldova 2022: -225

- Switzerland 2025: +214

- Ukraine 2021: -170

- Norway 2023: -164

- Malta 2021: +161

- Estonia 2025: -160

- Switzerland 2024: +139

- Serbia 2022: -138

- Finland 2021: -135

This list supports our previous findings, with almost every single entry hurt by juries felling in the ‘fun’ category.

Anomalies

Whilst there appears to be a strong trend, there are indeed some anomalies. There have been six occasions in the past five years where the jury has given over 50 points more than televoters to ‘fun’ entries.

- Malta 2021: +161

- Austria 2023: +88

- Malta 2025: +75

- Belgium 2023: +72

- Luxembourg 2024: +63

- Italy 2024: +60

Among these entries are Malta and Luxembourg – smaller nations who are often thought to struggle in televote due to fewer voting friends or diaspora. We also see Austria 2022, who went from finishing 2nd in the televote when performing near the end of their semi, to 22nd after opening the grand final. This highlights that, regardless of potential biases, juries do give support to smaller countries and reduce the impact of the running order.

Malta 2021 is also part of the small list of ‘fun’ entries which managed to crack a smile in the music professionals and score a top 3 in the jury vote. Joining this list are Croatia 2024 (3rd in jury vote; hurt by -127 points), Israel 2023 (2nd in jury vote; hurt by -8 points), and Spain 2022 (3rd in jury vote; helped by +3 points).

On the other hand, there is just one instance* where the jury hurt a ‘serious’ entry by more than 50 points: Poland 2022: (-59 points). Interestingly, this indicates that juries’ fondness for ‘serious’ entries is stronger than their dislike for ‘fun’ ones.

Jury impact on Eurovision winners

Below you can find the overall winners of each contest, as well as the individual jury and televote winners. We have also included the difference between the jury and televote points, showing whether the juries ‘helped’ or ‘hurt’ each entry.

2021

2022

2023

2024

2025

From this we can see that the jury currently has a far greater role in deciding the winner of Eurovision, with the jury favourite ending up being the overall winner in the majority of the past five editions of Eurovision.

We can also see that each year, the jury’s favourite was either a ‘serious’ or ‘other’ entry, whilst the televote’s favourite was always ‘fun’ or ‘other’ entry. The most successful technique for winning Eurovision overall appears to be sending an entry in the ‘other’ category, likely because it still appeals to televoters but avoids being hurt by juries as much.

It’s also worth mentioning the previous edition, 2019. Although the eventual winner of Eurovision 2019 was the Netherlands’ heartfelt pop-ballad, it was neither the favourite of the televote, nor the juries. Norway’s KEiiNO won both the televote in both their semi-final and the final with their Sami-inspired spiritual banger, reaching the top three in more than half of all voting countries. However, the juries were less impressed, ranking them as a non-qualifier in the semis and just 19th in the grand final, hurting them by -251 points and depriving them of a top 5 placing.

As for the jury vote, it was North Macedonia’s Tamara Todevska placing on top. The female-empowerment power ballad made the top three of 17 countries’ juries, giving them an +189 point boost compared with televoters, who put the entry 12th with 58 points. Whatsmore, if you remove scores from North Macedonia’s neighbours in the former Yugoslavia and Albania, the song is left with just 15 points from six other countries – which would put them 22nd in the televote. Of course, one could also argue that Norway benefitted from their Scandinavian voting partners. However, removing scores from their four nordic neighbours leaves them with 245 points, which would still put them in 3rd place.

In conclusion, there appear to be extremely strong patterns indicating that Eurovision juries do indeed favour Eurovision’s more ‘serious’ entries over ‘fun’ ones. So now the question is, what is causing juries to disagree so strongly with viewers at home?

Discussion: why do Eurovision juries give more points ‘serious’ entries?

Are ‘music professionals’ judging entries with their heads over their hearts?

Juries are given 4 main sets of criteria to focus on when judging an entry:

- Vocal capacity of the artist(s)

- Performance on stage

- Composition and originality of the song

- Overall impression of the act

This seems like a fair enough set of parameters to judge a good performance. But the question is, are the juries voting for their favourite, or are they voting for what they consider to be ‘high quality’?

Because jury members consider themselves music experts, they may be more likely to vote for entries they see as ‘high quality’ over what they actually enjoyed the most. Furthermore, by having their scores posted publicly alongside their name, they may be more cautious of highly ranking an entry that takes itself less seriously, as it risks harming their credibility as a music expert.

And could it be that certain genres are considered to be more sophisticated, and therefore ‘higher quality’ than others?

Does ‘silly’, ‘camp’ or ‘europop’ mean low quality?

When we look at our data of the top 5 entries that the juries have hurt the most over the past five years (Finland 2023, Moldova 2022, Ukraine 2021, Norway 2023, Estonia 2025), the overriding themes are a strong dance beat, elements of humour and ethnic instruments. Once upon a time, these elements described the most successful Eurovision entries – but now they appear to be things to be penalised for.

Let’s take the example of Norway 2023: the Nordic-enfused eurodance anthem “Queen of Kings”. Alessandra slayed her competition in the televote, racking up 216 points putting her in third place among viewers at home. On paper, there was no reason why she should match this in the jury vote: a slickly written and produced song, heaps of charisma, a dynamic stage performance and flawless powerhouse vocals – even including a speorg note! But regardless, the juries ranked her 17th with just 52 points. Why could this be? Well perhaps it was the genre itself.

Europop and dance-pop are simply not viewed as ‘high quality’ genres of music by many music professionals… despite being one of the most popular genres throughout the continent, and what the contest became famous and loved for. You cannot measure a song’s quality, but you can measure how much people enjoy it, via its televote popularity and post-contest commercial success. And after going on to chart in the top 20 in the majority of European nations (including a UK top 10!), Alessandra must have done something right.

On the flipside, we see genres such as ballad, mid-tempo pop and gospel repeatedly thrive among juries – even when the regular viewers of Eurovision didn’t think much of them. It appears that these are the genres considered ‘high quality’ by juries. Does more thought go into writing a ballad compared to writing a dance hit? Does it take more skill to produce moody mid-tempo pop compared with jovial ethno-pop? And even if it did take more time, does that make it ‘better’?

Do juries focus on vocals over song?

In the Eurovision Song Contest, one would think that the jury’s main focus is the song. However, that doesn’t always seem to be the case. This year, the juries gave a top 10 placing to the United Kingdom – a televote nul points song, whose tempo-shifting structure was far from the usual jury favourite. That said, the trio packed in three-part harmonies, vocal riffs and big belter notes, reminding us that vocal ability is not to be underestimated in the jury vote.

A good year to highlight this would be 2017. Four of the jury’s top five in the grand final were ballads, with the exception of a typical slick pop number from Sweden. Whilst two of these ballads were the televote winner and runner-up (Portugal and Bulgaria), the jury top 5 also included two ballads which were completely lost on viewers at home – Australia and the Netherlands. We can also add Denmark to this mix, who qualified for the final with just 5 televote points, thanks to a generous +96 point boost from the jury.

In total, Australia, the Netherlands and Denmark earned an impressive 375 jury points in the grand final. However, with televoters they only managed to muster up a measly 25 points between the three of them. Clearly the televote was not anti-ballad, as the two televote favourites were ballads… so ‘what the hell just happened’?

Unlike Portugal and Bulgaria, none of these three had any real commercial success with their entries. And whilst it’s not possible to measure how ‘good’ a song is, this does indicate that these songs simply were not popular among the general public. So why did they all score so high with the jury? Well, they were the perfect songs for showcasing vocal abilities.

Australia’s Isaiah had a smooth soulful voice, Denmark’s Anja Nissen could belt out those power ballad vocals, and Dutchies OG3NE sang with flawless harmonies. The same could be said for our British girlies Remember Monday. But were the juries truly evaluating the songs, or was their real focus on their vocals? Of course vocals are important, but should they be more important than the song itself?

Solutions: Possible changes to the jury system

Update the jury voting criteria

As previously mentioned, Eurovision juries use four criteria to evaluate entries: Vocal capacity of the artist(s); Performance on stage; Composition and originality of the song; Overall impression of the act. However, perhaps the first three are distracting from the final and arguably most important criterion: the overall impression of the act.

If juries were to purely vote on overall impression – which intrinsically includes all elements from song to staging to vocal – they would be more likely to give a ranking based upon genuine enjoyment, rather than a scientific assessment of the entries according to a list of specifications. The true magic of music is that it’s fully subjective – but adding criteria only encourages people to judge it objectively.

Change the jury composition

As previously mentioned, a jury made up of music professionals is more likely to vote for ‘safer’ or ‘jury friendly’ options because their names are published with their ranking, and thus their reputations are at stake. So why not shake things up by throwing in five more regular people who don’t work in the music industry?

Non-industry professionals are more likely to vote heart over head and give an honest judgement on entries, without barricades like musical snobbery or genre-bias. Furthermore, by having a larger jury, we are compiling a greater mix of opinions and finding a more accurate view of a country’s favourite entry. The greatest challenge with this, however, would be ensuring that an even bigger group remains corruption free.

But if juries rewarded fun songs more, would Eurovision become a ‘circus’?

It’s undeniable that if all entries were silly and camp, the contest may lose its reputability. However, in the past three editions of the contest (since juries were scrapped in the semi-finals), the grand finals have consisted of 11, 12 and 10 ‘fun’ entries respectively (see results section). So in other words, even without juries, these silly camp europop numbers are still a minority.

The likes of this year’s Australian and Irish entry tried to win Europe’s heart with catchy beats and playful visuals, but viewers still preferred a variety of other entries over them. In this year’s grand final televote, the bottom ten consisted of 8 ‘fun’ entries and just 2 ‘serious’ ones. Ballads won the televote fair and square in 2011, 2013, 2014, 2015 and 2017. Fun does not equal Eurovision success, and it takes something very special to win a televote.

It’s also important to note that if there are lots of similar entries, they divide their supporters and usually none of them excel. Take 2021, a year full of fun, female-led pop bangers. Despite strong fan support and lots of radio hit potential, the best televote placement for a europop entry was for Serbia’s Hurricane in 9th position. So even if ‘fun’ entries did see a higher prevalence at the contest, it would only be the really loved ones that would take the top spots, and the serious entries may even benefit as they would stand out more.

Amend the jury weighting

Many argue that the 50:50 jury-televote split is not fair, as juries often have such a clear first place that it’s an almost impossible mission for anyone else to win. In 2023, the juries gave Sweden a mammoth 163 point lead over the jury runner up, Israel. This meant that, despite Finland receiving 376 televote points (the second-highest televote score ever after Ukraine’s 2022 win) and Sweden getting not one single pair of douze points, it still was not enough to knock Loreen from the top spot. Similar happened the following year, when jury winner Switzerland was 147 points ahead of jury runner-up France. Sometimes, the jury advantage is simply too great for viewers at home to override.

But let’s look what happens to the results of the past five years if we amend the ratio to ⅓ jury votes and ⅔ televote (calculated by doubling the number of televote points)*:

Key remarks to take from the ⅓ jury results:

- We still see a mix of ‘serious’ and ‘fun’ entries in the top 5 each year, including the same overall winners in 2019 and 2021.

- However, from 2022-2025, we see new, ‘fun’ winners. In 2022 this is Spain (excluding Ukraine), who won neither the jury nor televote, but ended on top overall. In 2023 and 2024, the televote winners Finland and Croatia take the trophy, whilst the jury winners finish second.

- In 2025 we would have had a nailbiting tie between Estonia and eventual winner Austria. However, if we had not removed Israel from our analysis, it would have been them in the #1 spot.

Using this weighting, we still see jury favourites achieving a great overall ranking, but it’s the peoples’ favourite who win overall the majority of the time. This way, the jury is still rewarding entries that it sees as ‘high quality’, but not having such an enormous impact as to completely change the final result.

On the other hand, some may argue that this is a step too far, and that the latter three ‘fun’ winners would be too similar to each other. That said, it’s important to note that people like variety and don’t want the same thing to win every year; had Käärijä won in 2023, it’s unlikely that Baby Lasagna or Tommy Cash would have done as well in 2024 and 2025 respectively.

It’s also worth noting that, by increasing the weighting of the televote, the results are more susceptible to politically charged mass voting. Hence, if we put post-war Israel and Ukraine back into our results, we would have seen Ukraine win by a greater margin in 2022 and Israel snatch the top spot at this year’s contest. So before considering implementing this updated weighting, it’s probably best to wait until the EBU have found a solution to geopolitical voting influence of a scale that overshadows the audience’s musical choices.

Conclusion

It is undeniable there has been a huge disagreement between the jury vote and televote in recent years. From our data analysis, we can confirm that juries do indeed have a tendency to give more points to ‘serious’ entries and than ‘fun’ ones. To be precise, they give an average boost of +48 points per ‘serious’ entry, and a disadvantage of -26 points per ‘fun’ entry in comparison to televoters – but often these discrepancies are far higher.

There are likely to be multiple reasons behind these patterns. Genre-bias among juries may lead to ballads and mid-tempo entries to be viewed as ‘higher quality’ than others. Additionally, there may be a fear that voting for ‘fun’ entries may tarnish the music professionals’ reputation. Moreover, an overly strict following of the assessment criteria may encourage juries priorotise things like vocals above overall impact, and lead jurors to vote head over heart.

Despite all this, we have also seen that juries have benefitted the overall result in some ways. They supported our smaller nations who often struggle in the televote. They were also impacted less by the running order and, most importantly, geopolitical events.

We suggested a few different solutions. Firstly, removing the criteria, and asking jurors to create their ranking purely on overall impression and enjoyment. We also considered adding five non-music professionals to each jury, reducing biases and getting a broader scope of opinions. Alternatively, reducing the jury power to ⅓ of the vote would give an overall result that is more in line with viewers preferences… although it also makes the result more vulnerable to recent cases of geopolitical mass voting.

So now the question is: does the jury system need revising?

What we cannot ignore is the shift in authority: the power in selecting a winner has gone from the millions of viewers at home to 5-person juries. And after completing this analysis, we can be confident that the superior power of the juries is linked to the fact that, in the past ten editions we’ve only had two ‘fun’ entries win the contest (Ukraine 2022 and Israel 2018).

But is it in fact the right thing that music professionals decide the winner, as they know the most about music? Would victories for the televote winners have been distasteful and damaged the contest’s image? Do the results even matter as long as there is a good show?

One thing is for certain – as long as the juries continue to decide the winner, countries will increasingly focus on pleasing them rather than the viewers at home.

Could this turn songwriting into a science to please specific parameters, rather than musicians simply producing a product that they love? Will this create an increase in international songwriting camps and decrease in organic, locally made music? Might broadcasters become weary of selecting ‘fun’ songs as they have a built-in disadvantage? Or perhaps we’ll see a decrease in ‘eurotrash’ and song ‘quality’ will reach new highs?

So many questions, and so many opinions to hear from you. Vote in our poll below on whether you think the Eurovision jury system needs rethinking, and please let us know your thoughts on the matter in the comments below!

Hm, good article to read. I think the vibes voting for jury voting might be the best solution to give a good even playing ground to both the juries and televotes. Or, add a demoscopic jury to give three categories that can combine with the jury votes. Or better yet, add back the juries to semifinals to give a mixture of what songs are in the finals. I don’t know, I’m American, so I have zero saying power

iirc before the juries came back officially in 2009, we still had back up juries but they were random members of the public or fans, rather than industry professionals.

I think you could keep the 5 music industry professionals but add 5 fans to the jury as well.

Unrelated but I thought people needed to see:

https://eurovisionfun.com/en/2025/09/israel-ebu-proposes-a-deal-to-kan-to-resolve-ongoing-crisis/#:~:text=EBU's%20proposal%20to%20KAN&text=On%20the%20other%20hand%2C%20if,which%20KAN%20has%20reportedly%20opposed.

A NEUTRAL FLAG? Seriously EBU? GTF that means nothing. A neutral entry, still organised by KAN is still an Israeli entry.

Russia and Belarus don’t compete under a neutral flag, either should these.

Get them out NOW!

What bothers me about the juries is that most of them are pop music ‘experts,’ so they tend to rank only those songs highly, while non-pop entries get overlooked.

I’d rather see a system where jurors represent different genres based on the playing field, so each song can be judged by someone who actually understands that style.

That way, ethnic or non-pop songs would also be fairly evaluated.